Hi, In this short article we will explore the internal structure of a simple hello world module in the linux kernel, breaking down its anatomy and understanding how it integrates with the kernel.

Environment

- Kernel Version : 6.16.0

- Build Toolchain : clang 18, LLVM 18

- OS : Ubuntu 22.04 / Nixos (Any distro will work)

Basics

The Linux kernel is monolithic in nature. Monolithic kernels lack the extensibility and modularity, which can make the kernel bloated and difficult to manage. Linux kernel solves this problem with kernel modules.

A kernel module is an object file containing code that can be loaded at runtime and can be used to extend the functionality of the kernel. When a module is no longer needed, it can be automatically unloaded, thereby reducing the memory footprint. Modules give several advantages to the kernel, such as extensibility, modularity, low memory footprint, faster compilation, etc. Most of the device drivers in the kernel are implemented in the form of modules, which contributes significantly to the modularity and maintainability of the kernel.

Internally, the kernel consists of a loader that, when requested, can load and map this object file into its own address space. Once mapped, the module can call kernel symbols just like any other part of the kernel.

Having a modular kernel also allows companies to provide their drivers in the form of proprietary binary blobs. This way, the company can apply its licenses to the source code and is not obligated to release the source code. Whether it’s a good thing or a bad thing is a different topic (in terms of philosophy, security, etc.), but I guess companies have their reason for doing this.

Source Code

Let us now examine the traditional hello_world module and understand what happens internally.

// SPDX-License-Identifier: GPL-2.0

#include <linux/module.h>

MODULE_DESCRIPTION("A simple hello world module");

MODULE_AUTHOR("Gopi Krishna Menon");

MODULE_LICENSE("GPL");

static int __init hello_mod_init(void)

{

pr_info("%s: Hello World\n", KBUILD_MODNAME);

return 0;

}

static void __exit hello_mod_exit(void)

{

pr_info("%s: Unloading hello_mod\n", KBUILD_MODNAME);

}

module_init(hello_mod_init);

module_exit(hello_mod_exit);The code illustrates the fundamental structure of a kernel module. Its key components are :

- License Identifier (SPDX Identifier)

- Header File (module.h)

- Module Metadata (MODULE_DESCRIPTION, MODULE_AUTHOR,…)

- Initialization and Cleanup Functions

- Entry and Exit Points

License Identifier

The first line // SPDX-License-Identifier: GPL-2.0 indicates the license associated with the source file. Although linux kernel is primarily licensed under GPL, there are several drivers that have a different free license such as MIT, BSD etc. SPDX or Software Package Data Exchange is a freely available open standard that provides a clean and unambiguous way (one line) to indicate the license associated with the source file. If we didnt have the SPDX standard, the license for each of these source files would look something like this :

/*

* Copyright (C) 2025 Meow

* This program is free software: you can redistribute it and/or modify

* it under the terms of the GNU General Public License...

*/which is harder to read and can be ambiguous sometimes.

Header File

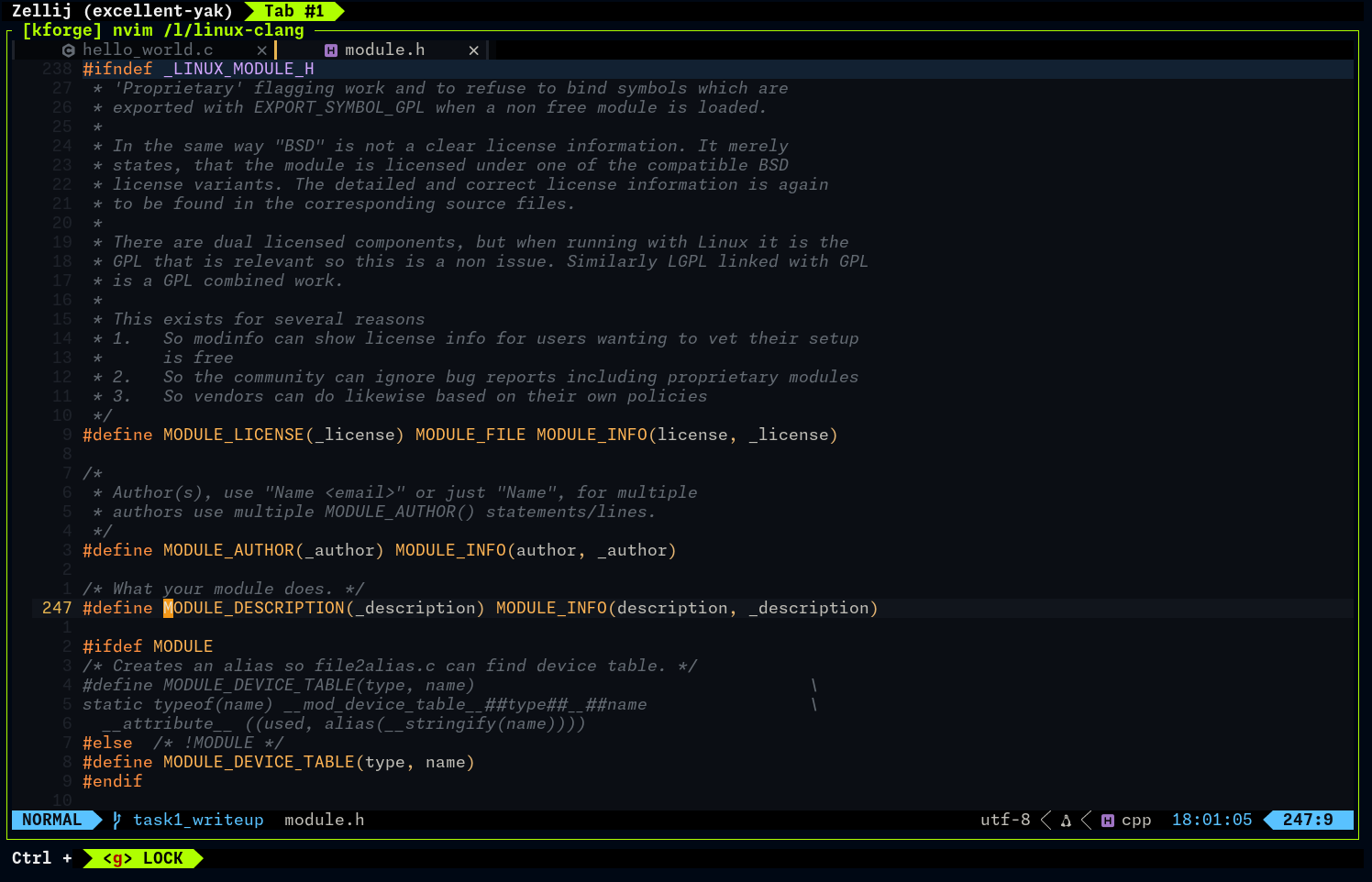

#include <linux/module.h>

This header provides the necessary kernel API’s and macros to create a kernel module. MODULE_DESCRIPTION, MODULE_AUTHOR and MODULE_LICENSE and several other macros are defined within this header file.

Module Metadata

The macros MODULE_DESCRIPTION, MODULE_AUTHOR and MODULE LICENSE define metadata about the module. This metadata is then embedded into the resulting .ko file that can be read by tools like modinfo or the kernel module loader.

So lets have a look at what these macros distill down to ultimately.

Looking at the definition of MODULE_DESCRIPTION, MODULE_AUTHOR or MODULE_LICENSE we can see that all of these macros boil down to MODULE_INFO.

/* Generic info of form tag = "info" */

#define MODULE_INFO(tag, info) __MODULE_INFO(tag, tag, info)Here we can observe from the comment that the module info is represented in the form of tag:value pairs.

#define __MODULE_INFO(tag, name, info) \

static const char __UNIQUE_ID(name)[] \

__used __section(".modinfo") __aligned(1) \

= __MODULE_INFO_PREFIX __stringify(tag) "=" info

Here UNIQUE_ID ensures that the variable names never clash. Basically it appends UNIQUE_ID prefix to the variable and a unique number as the suffix to the variable. This is necessary because, if we look at the previous code snippet we can see that we pass tag as the name parameter to the macro. Therefore if invoke the macro multiple times (like multiple authors), then it could result in variable name collision which can be avoided using this.

But the variable name is not important here. Whats important is that the data of this variable is added into .modinfo section and the data itself is tag=info. Now modinfo section is very important as it contains the module information.

In case of our hello world module, if we generate the LLVM IR for this module, we can see that this is generated.

To generate the IR for this kernel module what I did is

make V=1 LLVM=1 M=custom_modules/hello_worldFrom this I extracted the line containing clang invocation and copied that to a seperate bash script where i gave emit-llvm -S option to clang and specified it to generate hello_world.ll file.

@__UNIQUE_ID_description481 = internal constant [40 x i8] c"description=A simple hello world module\00", section ".modinfo", align 1, !dbg !0

@__UNIQUE_ID_author482 = internal constant [26 x i8] c"author=Gopi Krishna Menon\00", section ".modinfo", align 1, !dbg !7

@__UNIQUE_ID_author483 = internal constant [12 x i8] c"author=Meow\00", section ".modinfo", align 1, !dbg !14

@__UNIQUE_ID_license484 = internal constant [12 x i8] c"license=GPL\00", section ".modinfo", align 1, !dbg !19

As we can observe, the data is stored in the form of tag:value pairs. Also I added additional author to show you how UNIQUE_ID is helping here. Now if we look at the hexdump of .modinfo section via readelf, we can see that the data is stored in the same manner inside the section:

readelf -x .modinfo custom_modules/hello_world/hello_world.k

Hex dump of section '.modinfo':

0x00000000 64657363 72697074 696f6e3d 41207369 description=A si

0x00000010 6d706c65 2068656c 6c6f2077 6f726c64 mple hello world

0x00000020 206d6f64 756c6500 61757468 6f723d47 module.author=G

0x00000030 6f706920 4b726973 686e6120 4d656e6f opi Krishna Meno

0x00000040 6e006c69 63656e73 653d4750 4c006e61 n.license=GPL.na

0x00000050 6d653d68 656c6c6f 5f776f72 6c640064 me=hello_world.d

0x00000060 6570656e 64733d00 73726376 65727369 epends=.srcversi

0x00000070 6f6e3d32 46374643 31393532 44453044 on=2F7FC1952DE0D

0x00000080 44453443 30454638 45370076 65726d61 DE4C0EF8E7.verma

0x00000090 6769633d 362e3136 2e30636c 616e672b gic=6.16.0clang+

0x000000a0 20534d50 20707265 656d7074 206d6f64 SMP preempt mod

0x000000b0 5f756e6c 6f616420 6d6f6476 65727369 _unload modversi

0x000000c0 6f6e7320 00726574 706f6c69 6e653d59 ons .retpoline=Y

0x000000d0 00

Running modinfo, we can see the .modinfo data

modinfo custom_modules/hello_world/hello_world.ko

filename: /linux_work/linux-clang/custom_modules/hello_world/hello_world.ko

description: A simple hello world module

author: Gopi Krishna Menon

license: GPL

name: hello_world

depends:

srcversion: 2F7FC1952DE0DDE4C0EF8E7

vermagic: 6.16.0clang+ SMP preempt mod_unload modversions

retpoline: YNote : In the above code you can observe that there is vermagic, which is also present in the .modinfo section. Basically if you load a module and vermagic of module does not match whats there in the kernel, it wont load the module. So modules built for one kernel is not compatible with other kernel.

static int check_modinfo(struct module *mod, struct load_info *info, int flags)

{

const char *modmagic = get_modinfo(info, "vermagic");

int err;

if (flags & MODULE_INIT_IGNORE_VERMAGIC)

modmagic = NULL;

/* This is allowed: modprobe --force will invalidate it. */

if (!modmagic) {

err = try_to_force_load(mod, "bad vermagic");

if (err)

return err;

} else if (!same_magic(modmagic, vermagic, info->index.vers)) {

pr_err("%s: version magic '%s' should be '%s'\n",

info->name, modmagic, vermagic);

return -ENOEXEC;

}

err = check_modinfo_livepatch(mod, info);

if (err)

return err;

return 0;

}Module License Enforcement

The MODULE_LICENCE macro is not just for display, it has runtime implications. Basically

- If you declare

MODULE_LICENCE(GPL), the module is treated as GPL compatible - If you declare

MODULE_LICENCE(Proprietary)or leave blank, it is not GPL compatible (meaning you cant access kernel symbols which are markedGPLonly usingEXPORT_SYMBOL_GPL).

Whatever license we have supplied to this macro can impact what symbols can we access from the kernel. So basically if we have used PROPRIETARY licence, then we cannot call or access any symbols from the kernel which are marked GPL only (using EXPORT_SYMBOL).

Initialization and Cleanup Functions

The functions hello_mod_init and hello_mod_exit are initialization and cleanup routines for the module.

static int __init hello_mod_init(void)

{

pr_info("%s: Hello World\n", KBUILD_MODNAME);

return 0;

}

static void __exit hello_mod_exit(void)

{

pr_info("%s: Unloading hello_mod\n", KBUILD_MODNAME);

}

You can think of these as analogous to setup and teardown functions.

- hello_mod_init is called when the module is inserted into the kernel. It can be used for setting up resources required for this perticular module

- hello_mod_exit is called when the module is removed from the kernel. It can be used for cleaning up any resources acquired during initialization.

Inside the init and exit function, I am simply printing “Hello World” and “Unloading hello_mod” to the kernel ring buffer. Return value of 0 indicates success as usual. If the initialization fails for some reason, you can also return the error code such as -ENOMEM, -EINVAL which the kernel will handle accordingly.

The __init and __exit are annotations which instruct the compiler to place these functions in special section .init.text and .exit.text. The kernel can take this as a hint and can remove the code in these sections when the initialisation or removal is complete. This can help freeing up memory resources.

Finally the macros module_init and module_exit are used to register these functions. module_init basically specifies the driver initialisation entry point. If the module is builtin (compiled into the kernel), then it will be invoked during do_initcalls(), otherwise it will be invoked by do_init_module during module loading

...

freeinit->init_text = mod->mem[MOD_INIT_TEXT].base;

freeinit->init_data = mod->mem[MOD_INIT_DATA].base;

freeinit->init_rodata = mod->mem[MOD_INIT_RODATA].base;

do_mod_ctors(mod);

/* Start the module */

if (mod->init != NULL)

ret = do_one_initcall(mod->init); /* Here */

if (ret < 0) {

goto fail_free_freeinit;

}

if (ret > 0) {

pr_warn("%s: '%s'->init suspiciously returned %d, it should "

"follow 0/-E convention\n"

"%s: loading module anyway...\n",

__func__, mod->name, ret, __func__);

dump_stack();

}

/* Now it's a first class citizen! */

mod->state = MODULE_STATE_LIVE;

blocking_notifier_call_chain(&module_notify_list,

MODULE_STATE_LIVE, mod);

...For exit, if it is not built into the kernel, it will be invoked by delete_module syscall which is invoked by rmmod

...

/* If it has an init func, it must have an exit func to unload */

if (mod->init && !mod->exit) {

forced = try_force_unload(flags);

if (!forced) {

/* This module can't be removed */

ret = -EBUSY;

goto out;

}

}

ret = try_stop_module(mod, flags, &forced);

if (ret != 0)

goto out;

mutex_unlock(&module_mutex);

/* Final destruction now no one is using it. */

if (mod->exit != NULL)

mod->exit(); /* HERE */

blocking_notifier_call_chain(&module_notify_list,

MODULE_STATE_GOING, mod);

klp_module_going(mod);

ftrace_release_mod(mod);

...

So yea, this completes the dissection of a simple kernel module, in future articles, I will talk about other macros such as module_param, module_softdep, module_weakdep etc.